Most organizations simply don’t have enough skilled people to accomplish all the work they want to do in the time in which they wish to accomplish it. This is true in every area of business, but it’s particularly true when it comes to balancing the competing priorities of running the business and transforming the business.

Organizations have been living with this problem for years and have simply accepted it as the norm. But things are changing. Digital business and the competitive environment that comes with it makes it imperative that companies become more thoughtful about where and how they chose to invest the time of their precious human resources.

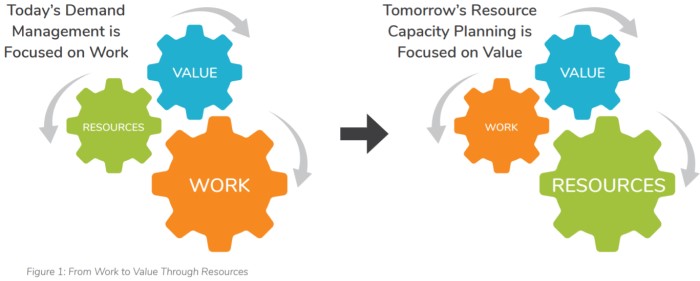

Today, as shown in the left-hand side of Figure 1.0, the focus of many organizations is in planning for the maximum work that they hope the “system” (in our case IT) can handle. The problem is, too much work without the resources to complete it ends up overwhelming the system and value is minimized.

We think there is a better way. On the right side of Figure 1.0, we propose that if the focus shifts away from the perspective that work creates value, to a system where the right resources completing the right work creates value, then the overall amount of value received from the people doing the work (resources) goes up.

We all know that there are two kinds of work that flow through any system: the work that generates 80% of the value and the work that sucks up 80% of the time for the remaining 20% of the value. If we postulate that most companies have at least 20% more work in their system than it is possible to complete, what happens is that the system becomes inefficient. The net result is not only that the 20% that was overbooked is not delivered, but the fragmentation of being overbooked can drive the under-delivery up by another 20%. This situation doesn’t need to happen.

The solution to the problem above requires two actions. The first will be the hardest for most companies: Don’t allow work into the system that can’t be resourced. Secondly, ensure you know how much work your current resources can accomplish.

Luckily for organizations that have a tough time saying no (we understand that hope springs eternal), Resource Capacity Planning (RCP) tools are available and are easier to use than ever before. There are also simple models that let you conceptually right-size the amount of work you want to let into your delivery system without needing to start by saying no to specific projects.

Step 1: Beginning the journey to RCP

Obviously, the specifics of the model will be slightly different in each business unit (IT, Product Development, etc.), but the basics will be the same. We’ve chosen to use IT as our first example, primarily because IT is often the choke point for most organizations on their transformational journey toward becoming a digital organization.

Where do you start? By not jumping into the deep end of the pool. Getting too detailed too early will overwhelm almost any organization. In our work in helping organizations become more agile across the enterprise, we’ve uncovered a common sense “secret”—always start with a model of where you want to end up. For most companies, the goal is to get the right people working on the right things at the right time. The only question is how you will quickly determine the right number of resources to dedicate to the right type of work.

The answer is to build a high-level model. The model we are recommending is a direct result of meetings with corporate IT organizations across the globe. We quickly found that if we didn’t set some guardrails around the discussion of getting a handle on IT demand management, we’d never get out of the weeds.

Activity 1: Model where you want to invest your FTEs

This activity intends to build a model that shows how you want to distribute your people based on operational needs and strategic needs. On your first pass, you will simply be getting what you think is a realistically aspirational number.

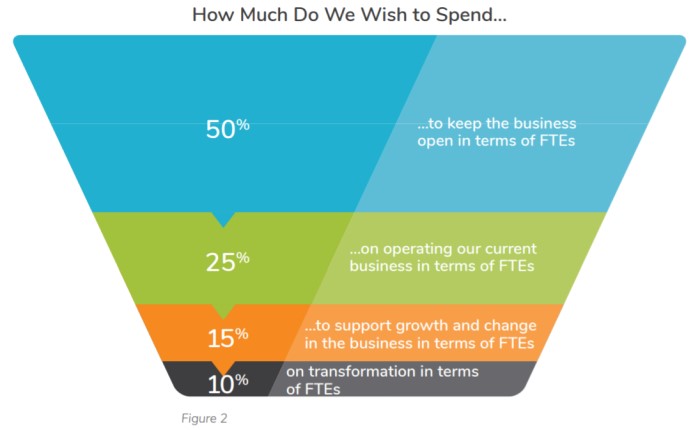

In Figure 2.0, we’ve broken the IT resource pools into four common categories:

The first category is keep the lights on. No matter how tempted you might be to skip this category and roll all your operating FTE’s into the “operate the business” category, our experience is that it doesn’t end up saving any time. Instead, it often ends up creating a perception that the organization has more people available to do work then they have. In IT this category would generally be those individuals who keep the servers up and the help desk running with enough resources to fix priority one bugs for 30 days. It does not include resources to do regularly scheduled maintenance or to do upgrades. This category is very limited, and most of the individuals in these jobs are specialists in their function.

Consider the use of this category a best practice that will save time, effort and energy as you move through the politics of resourcing your portfolio. For whatever reason, we’ve consistently seen organizations that don’t break these people out at the beginning finding themselves defending why these resources aren’t fungible (assignable to other work).

The next category is operational support of the current business. In an IT context, this category would be limited to support of current systems. A like-for-like replacement of a current system would also be included in this category. For companies that are converting to a product-based approach from a project-based approach, this would be all the people you have on fixed teams that keep the systems operating. Completely new work would be grouped in the next category.

The third category is future-oriented work to continue to grow the existing business. The decision to use this category will largely be a political one. For some companies, it made their discussions clearer (even if they were louder). For others, it’s a distinction signifying nothing. Gartner coined the term “grow the business” to cover this category, but we’ve found mixed results on what has gotten implicitly lumped into it. As guidance, use it if your company is focused on market share growth or significant investment in upgrading current products.

The fourth category is transform the business. This category should be reserved for the support of new products and services. This is where your “digital transformation” oriented people would be placed. Whether it’s big data, IoT, or some other new way to monetize your future offering, put it here.

An optional fifth category is innovation (not shown in Figure 2.0). Digital business should encourage companies to set aside headcount for innovation, and some are, but in our experience, innovation is generally a specifically planned investment with a dedicated headcount and isn’t really in resource contention with the other four categories.

How long this activity will take depends on your company. We’ve routinely done it with CIOs in half a day. The key is to start with guidance from executive management if it’s available or a guestimate of actuals if it isn’t. It’s important to stress that this is a model. There is a 100% guarantee that the numbers will change as the consequences of trying to live with these allocations become clear, but that is exactly the situation you are trying to create by doing resource capacity planning. Precision is your enemy at this point.

Activity 2: Map FTE numbers to skill types

Now that it’s been determined that IT can be broken into four categories, the next step is to identify the skills/roles of the people in each category.

You will need a small team of people to do this. The most successful approach we’ve seen is to pick a few senior people in IT who are politically savvy and pair them up with a few trusted resources from outside of IT (consultants, internal change management people, senior financial analysts or senior HR people).

With the Keep the Lights On group, all the organizations we have worked with started by identifying the real people and then working backwards to skills. This category is small, and if you can’t name names, there is a problem.

With the Run & Grow the Business categories, determining FTE roles and skill types is generally quite simple—ask the department managers and check the HR records. Pay attention to whether expertise plays a significant part in the descriptions you get from the various managers. In some cases, a developer is a developer, but in others, a developer is a wizard who knows Python, Ruby on rails, C sharp and five other things. The quick-and-dirty workaround is to create new role/skill types like Java developer or possibly just a multi-skilled classification.

The next category of future-oriented work will often require identifying an FTE with a skills classification that doesn’t currently exist in your organization. Get HR to help you define the right hiring description so there isn’t confusion later.

Activity 3: Enter FTE and bottleneck resources into the RCP system

In the previous exercise, you identified the roles/skill types by which you will be designating FTEs, and you also counted noses to ensure that you have real people who primarily fill that FTE role. This means that if you have 500 people on your staff, you should have no more than 500 FTEs in the system.

The next step is to enter a small number of people (by name) who are bottleneck resources. Every organization has at least one bottleneck function and a few bottleneck people. In some organizations, the bottleneck function is security, while in others it’s application DBAs. We’ve chosen these two functions to make a specific point: Based on our experience, we’ve often found that security can become a bottleneck due to a process design as well as a shortage of people, while apps DBAs are generally a bottleneck due to a shortage of people within the function.

The third form of bottleneck resource is the man or woman who knows everything about everything. Every initiative starts their resource request list with this individual’s name at the top and even if they don’t get the person assigned, they still bring all their questions to this individual.¹

Activity 4: True up your current in-flight process

In a perfect world, you would true up every project in your portfolio and understand what would be possible to achieve if every project was resourced adequately, but we don’t live in a perfect world. The more streamlined version of this exercise is to:

- Identify your top 10 strategic priorities and completely update the project plans that are designed to deliver the projects as quickly as is possible. Pay attention to the resources that are now being requested as opposed to those already on the project.

- Plan on canceling or completely re-justifying any project that is more than six months over its initial due date.

- If you don’t have the necessary resources to complete your top 10 strategic priorities in the shortest amount of time, cancel/postpone more projects.

- Declare your organizational house clean and don’t let anyone lift any of the rugs.

Activity 5: Map current in-flight activities to FTE or named resources and analyze the results

This step is where the rubber meets the road. At the start of this activity, you have a better idea of how many resources it will take to finish your critical projects in a timely manner, and you have removed all the zombie projects from your delivery portfolio. From this point, mapping your FTEs should be largely a data entry exercise, with one exception: NO FTE can be assigned to more work than your utilization model allows. Some companies use 85% (aggressive), and others use 65% (at the low-end). Also, you need to stop when you’ve reached capacity regardless of how many in-flight projects are still on the list.

The more out-of-true you are (between work and available resources) the more we recommend making this effort with FTEs first rather than named resources. Information tends to leak; stakeholders tend to panic. Since the first pass is only a pass, it’s best to keep the information under wraps. This is one of the reasons we strongly recommend that you have a core team do this exercise rather than delivery managers. Once you see the plan with FTEs, you can work on any necessary adjustments and the messaging to the people whose projects will be delayed or canceled.

Activity 6: Decide if you want to use RCP as a planning tool or an execution tool

Organizations can get tremendous value out of just using RCP as a planning tool. Simply by ensuring that the portfolio doesn’t exceed actual resource capacity by more than a few percent, we’ve seen smaller organizations gain 90% of the value achievable. Larger organizations will eventually need to move on to Step 2 because they will need to formally recognize and plan for more detailed information about their workforce (smaller companies know their people).

Step 2: Moving beyond the plan to planning to execute

Let’s be clear: Having a solid plan that matches capacity to planned work would leave any company better off than 80 or 90% of their competitors, but all those gains can be destroyed by slipping back into the trap of not executing with commitment. In hundreds of discussions with organizations around getting better performance from investments in internal initiatives, we found that many organizations refused to even embark on the RCP journey solely because they knew their organization didn’t have the appetite to improve their execution performance (why improve your ability to plan when you won’t execute the work to the same standard you just planned?).

During this step in the RCP journey, we’ll outline some improvements that we’ve found have helped build a new performance-based culture.

Activity 1: Begin with a shared agreement on value

In the digital world, a straight financial ROI doesn’t cut it for most internal investments. Unless an organization has cutting costs to stay in business as its top corporate initiative, even cost reduction must compete for resources in the new digital marketplace.

While every organization will have a slightly different definition of value, we have found “contribution to strategy” to be the most flexible definition of value possible without giving up measurability. Why do organizations need a new value marker? To move the investment selection process from “Is it good?” (therefore, we’ll prioritize it) to “Is it required now to achieve our goals?”

“Now” is a wonderful word and it’s the gold standard when it comes to RCP. To earn the label of now, an investment must prove its position in a sequence of events designed to create a specific future. To clarify, most IT portfolios contain investments that are the equivalent of building the roof when the foundation hasn’t even been poured.

We should highlight at this point that two of the reasons the “roof” initiatives sneak in are politics (the squeaky wheel) and the inability of IT to show clearly the true opportunity cost of building the roof before the foundation. With RCP and a new definition of value, building the roof for a building no one has even agreed to can be measured in the cost of delay in reaching a strategic milestone.

Activity 2: Begin putting a hard upper limit on investments equal to their value to force critical decisions

If an initiative requests a million-dollar budget at the start, does that mean it is worth two million? What about 5 million? Over ten years we talked to hundreds of organizations that proudly told us they used stage gates so that they would approve the current budget for an ongoing project. The assumption was that when the budget got to be beyond value, the governance board could choose to kill it. Of course, this rarely if ever happened; instead, a 1M investment ended up costing 4M and taking six months to a year longer. As an isolated incident it wouldn’t matter, but with a shared labor pool everything is inexorably connected.

For example, if we assume investment B was important enough to get the A team assigned to it at the start, what happened to project D (that also deserved the A team) when it was supposed to start? The answer is that part of the A team will also be assigned to the D team. And when investment F starts, and investment A still isn’t finished, the most talented of the A team will find themselves working on three investments. At this point, the people assigned to investment B are demoralized and their productivity is suffering, which pushes out the project even further, and project G hasn’t been able to start at all.

With RCP in place, all of this becomes much more transparent. When it’s clear project B is caught in scope creep, part of the decision of whether to extend or end the project can be made by looking at the impact of the extension. In the case we described, project D is just as important if not more important than project B, so project B can be wrapped up.

What if project B had been mission critical and the new work was required? We’ve seen this situation several times in Product Development environments, and the response has always been very different than in IT. In one case, the CEO of the company stepped in as the sponsor, and all the resources were indefinitely seconded to the project. The remaining projects in the portfolio were then reevaluated and either eliminated or additional staff was brought in to keep them on track.

Activity 3: Invest in a resource management capability to ensure people are being assigned to do the optimal work they are capable of

As organizations become more mature in the RCP planning practices, it becomes possible to tie RCP to an individual’s skill developmental growth. It also becomes possible to anticipate and begin retraining staff to meet future skill-oriented demands. Professional service firms do this today because it’s tied directly to their revenue growth, but it’s been a hard problem to solve internally in most companies. The good news is that there’s been a growing trend among organizations to begin adopting and investing in the role of a resource manager. We’ll cover the resource management role in more detail in the next section.

Step 3: Executing in the face of reality by developing contention protocols

In steps one and two, we covered identifying resources and capturing their skills. We also confronted and theoretically worked through some of the more obvious planning constraints, but until now we haven’t drilled down into the details of how to make this work in an environment where there are still deeply embedded bad habits supported by vicious feedback loops.

In step three we need to focus on human behavior and company culture. Most people don’t think too much about their company culture, especially since most organizational leaders don’t feel that they have the power to change things. The truth is organizational culture change is NOT a unilateral, top-down process. Culture can change from the bottom up, and it can change from the middle out. Culture is also NOT monolithic across an organization. Marketing can have one culture, IT can have a different one, and Product Development might have a third completely different culture.

Implementing RCP through the first two steps will put your organization solidly on the road to building a culture that supports creativity and operates more effectively, but people still need to know how to handle conflicts around priorities in their day-to-day life. The answer to that question is a human systems problem and not a technology system problem.

It’s easy to come to the conclusion that the solution to both the employee disengagement problem and the productivity problem is to simply ask people to work smarter, and that’s true as far as it goes. The only problem is that there are structural workplace impediments to working smarter that must be removed.

Let’s take the most common example: People perceive that they are spread too thin and that their personal attempts to prioritize their work have political ramifications.

How is an employee supposed to know which is more important? Is it the P1 bug on a system that supports 15 users in the company or completing their current assignment on the company’s top IT priority? Having witnessed this situation in multiple companies worldwide, the usual answer is the P1 bug. Now imagine there is a variant of this happening with every employee in the organization every day. Eventually, people become frustrated because they are constantly being interrupted/ prevented from doing the work they perceive is high value to do work they perceive is of low value or simply a waste of time (administrivia). We once walked into a software development area and saw bright yellow crime tape blocking the entrance to a developer’s cubical. When we asked the manager what was going on with the tape, the answer was, “It’s the only way he thinks he can effectively tell everyone to leave him alone so he can get some work done.”

Now that we’ve painted a bleak picture of the reality of the global workplace, what can we do to fix it? After all, we’ve already matched work in-flight to the people available at a gross level, and we’ve fine- tuned the assignment of the work to match an individual’s skills and interests. How do we keep things on track on a daily basis?

While there is a long list of things we’ve suggested to completely solve this problem, we are only going to focus on what we consider the top two actions in this section of our white paper.

The first solution is to enable communication. The second solution enables better real-time decision making.

In theory, when an employee has a conflict between the work they are being asked to do and the work they can do, they are supposed to escalate to their direct supervision. Unfortunately, this rarely works because it’s generally the supervisor who created the problem in the first place by introducing some new request into the schedule without having the authority to remove any other work from the queue.

We mentioned resource managers as the secret ingredient in RCP, and here is where we will see their true value. In the case of a conflict that the employee can’t handle herself, the solution would be that she escalates to the RM, who then forces the project manager and the supervisor to talk to each other and work out the issue.

If you are tempted to say this is an unnecessary role because the supervisor and the PM could just do this themselves, the answer is of course they could, if it was their skill set and if it was in their interests. Some situations require a neutral third party at the beginning of the process. The good news is that after the RM has forced this type of meeting several times one of two things usually happens: The supervisor or the PM learns to go to their counterpart first and make the request instead of going straight to the employee, or it becomes painfully obvious there is a fundamental problem with either the supervisor or the PM.

The key to making these negotiations go quickly and effectively is to establish a protocol of exchange of value. Our solution has always been to keep the discussion focused on a trade of hours of work. If the supervisor needs something done urgently that is unplanned, the going assumption is that they request the time now at the cost of giving up time that was allocated to them later. Let’s take a clearer example: say the employee is SME from the business. Clearly, they have a 40 hour a week “day” job, but they’ve also been assigned to the project 10 hours a week. If the supervisor needs the employee back for the entire week, then the project gets 20 hours next week. If the project needs the employee for 20 hours one week, then the employee won’t work on the project next week. Obviously, this example is overly neat, but it provides a “fair” place for all negotiations to start.

Of course, hiring resource managers and improving communication skills won’t be effective if the over-committed individual doesn’t participate as well. The model above is one we use to work with individuals about improving their productivity and their enjoyment at work. When we begin the discussion, we ask people to focus on how they work and how much work they can get done in a day. We always ask them to keep a personal time log of what they did during their day, including things like time spent on Facebook, for at least a week. We then debrief the results. The goal is to establish a reasonable baseline and to identify any problems or unconscious distractors. The next subject is determining what excites them at work. For the most part, people love feeling useful and desperately want to know they completed work that their organization considers important. At the end of the process we discuss their plan for developing their mastery, however, they wish to define it.

We’ve done this exercise with web designers, tech writers, financial analysts, developers and mixed groups of all disciplines. The results are always the same. Some people hate their job and need to leave. Some people need to solve some personal problems with a therapist. The majority of people just want some level of order in their day (which RCP can provide), someone to help them negotiate conflicts (which RMs can provide), and finally, but no less importantly, they want access to training and a decent career development plan.

Conclusion

The goal of this white paper has been to provide an experiential summary of the benefits and the complications that you will experience on your journey toward stellar resource capacity planning. How important is resource capacity planning for your organization? Our answer is that it is one of two absolute necessities for every organization if they want to be successful in the future. The other is, of course, portfolio management. Fundamentally, we believe success in the Digital Age will shift the focus slightly from money to resources. Money is something most companies have. Talented, smart people doing the right work to create new innovations is something only successful companies have.

To download “STELLAR RESOURCE CAPACITY PLANNING IN THREE STEPS: Seamlessly Ensuring the Right People Are in the Right Place at the Right Time,” simply click the button below.

More Information

Tempus Resource allows users to:

- Run powerful “what-if?” scenarios in real time

- Quickly gauge over and under-allocations of resources

- Create fast, intuitive infographic data

- View the full project portfolio in one place

- Work with stand-alone data, or import data from management tools such as Project Server

For more information about Tempus Resource please contact:

Phone: 877-880-8788

Fax: 866-495-1734

Email: info@prosymmetry.com

Website: ProSymmetry.com

Bibliography

¹One organization we helped implement the concepts we are discussing here originally called us in because Edgar (their indispensable bottleneck resource) was in the hospital with a heart attack.

To download “STELLAR RESOURCE CAPACITY PLANNING IN THREE STEPS: Seamlessly Ensuring the Right People Are in the Right Place at the Right Time,” simply click the button below.